Sustainable Farming Techniques with Farmer Lee Jones

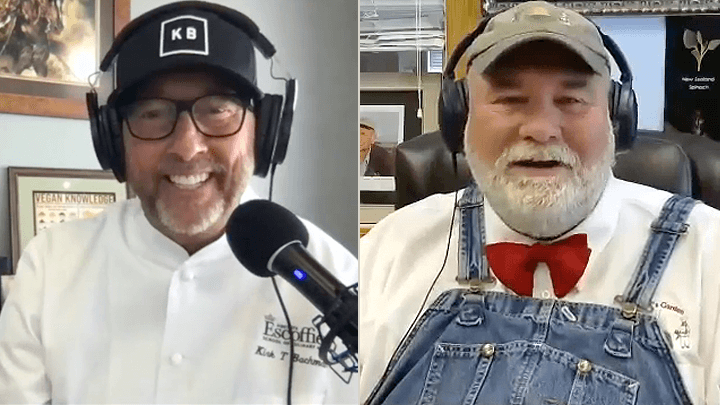

In this episode, we speak with Farmer Lee Jones, a speaker and expert on farming who is part of the founding family of “The Chef’s Garden” — a farm that uses innovative technology and traditional farming techniques to deliver high quality produce to some of the world’s leading chefs.

Farmer Lee places a big emphasis on following the natural rhythm of Mother Nature and the ability to look at nutrition on a seasonal basis.

He has appeared on ABC World News and as a judge on the Food Network’s Iron Chef America, Restaurant: Impossible. His many awards include The James Beard Foundation’s “Who’s Who in Food & Beverage” and being named as one of The Daily Meal’s “60 Coolest People in Food” for several years in a row.

Listen as we chat with Farmer Lee about sustainable farming techniques, genetically-modified produce, working with high-level chefs, and his life as a farmer.

Watch the podcast episode:

Don't Miss The Next Podcast Episode!

Get the latest episode of The Ultimate Dish delivered right to your inbox every week.

Email Address:

Jump to a Section

- Full Transcript

- The Uncertainty of Weather

- Supporting Students

- The Importance of Locale

- A Brief History of Farming in the U.S.A.

- Benefits of Being Old School

- Thoughts on Chefs who Elevate the Game

- The Necessity of Tech

- Seeds of Hope

- A Handful of Successes

- Product with Purpose

- Farmer Lee's Ultimate Dish

- The Importance of Locale

Episode Notes and Resources

TRANSCRIPT

Kirk Bachmann: Hi everyone. My name is Kirk Bachmann, and welcome back to The Ultimate Dish. In today’s episode, we’re speaking with Farmer Lee Jones, and speaker, expert on farming, and part of the founding family of The Chef’s Garden, a farm that uses innovative technology and traditional farming techniques to deliver high quality produce to some of the world’s leading chefs. Farmer Lee has appeared on a judge on the Food Network’s “Iron Chef America,” “Restaurant Impossible,” and ABC World News. His many awards include the James Beard Foundation’s award for Who’s Who in Food and Beverage and being named as one of The Daily Meal’s 60 Coolest People in Food for several years.

Join us today as we chat with Farmer Lee about farming techniques, working with chefs, sustainability, and life as a farmer.

Welcome Farmer Lee! Thank you so much for being here. How are you?

Farmer Lee Jones: Doing great! Thanks for having me on.

Kirk Bachmann: Absolutely. One of my favorite people in the world, right there. There he is!

Farmer Lee Jones: Back at you, buddy!

The Uncertainty of Weather

Kirk Bachmann: What’s happening on the farm today? Weather? Harvest? Everything?

Farmer Lee Jones: Everything. We’ve had plenty of rain in August. Ample. That being said, we’re planting in the top one inch of soil every single week. Even though there’s a lot of moisture down below, that top one inch gets dry. We plant every week because we want to have that continuous supply of quality products at the right size, at the right stage so that when chefs around the country and around the world call in and want a petite Sylvetta arugula, we can go out and harvest that. So even though there is moisture down below, that top one inch gets dry and we have to irrigate.

Interestingly enough, the temperatures have been record heat in July of 2021 and throughout the world. Hottest month in history, which certainly lends to supporting the global warming issue. The seeds have to be warm enough to be able to germinate, but they can also get too hot to germinate. So we find ourselves planting right at dusk as the sun’s setting, and then watering to bring the temperature down. Then watering again to bring that temperature down in the morning to get them to sprout. They can get too hot to germinate them.

Kirk Bachmann: There’s so much science to it. Not to go down Farming 101, but, boy, you have to pay attention to the weather patterns, future weather patterns. Is there always a Plan B when it comes to farming, just in case something doesn’t go as planned.

Farmer Lee Jones: I will guarantee that things will not go as planned. That’s part of Farming 101. Plan B is be prepared for the fact that things are going to go wrong.

One of the big things is excessive rain. People as they drive by fields probably don’t understand that there is what we call tiling in the fields. It used to be dug by hand. Maybe some folks have seen them and not even known what they were. They were orange in color. You could get them in two-inch, three-inch, four-inch, five-inch, ten-inch. Usually they were five-inch and they are one foot long.

You would dig at the highest point in the field and always make sure you were going down, and you’d drain to a creek bed. The water, when it comes down through the soil, can get into those tiles. You don’t seal them. You just put those tiles one against the other. The water can go into those tiles and drain. It’s expensive to put it in, but it’s even more expensive NOT to put it in. You could go nine years and say, “You know what? I didn’t need that tiling!” And in the tenth year, it puts you out of business. The old saying was, “You pay for tiling whether you put it in or not.”

Traditionally, you put it about every 60 feet. Some places will put it 40. On our farm, because it’s so specialized and so much hand work, we’re actually putting the tiling every 10 feet throughout the whole farm to try to get that water off. If you get that three-inch torrential downpour in an hour, you have an ability to get rid of it quickly.

Kirk Bachmann: That makes sense. And the tiling is there constantly. It’s always there.

Farmer Lee Jones: You put it in the ground, and it stays there. It’s below where you might hit with equipment, a plow or a disc. You know when you hit one, because then you’ll have this torrential hole, and all the water will drain. You’ve got to go in and patch it.

Supporting Students

Kirk Bachmann: First and foremost, I would be remiss if I didn’t say thank you for all of the love that you give back to the students of Escoffier. We visit every few weeks or so. We jump on and talk to student. Just last week you drove all the way up to Chicago to participate in an event with Escoffier students and others. It’s so appreciated, and I want you to know that. I also want to recognize the fact that you’re so selfless and humble when it comes to your time. You are a farmer. You are constantly busy. It’s 24/7, right. There’s no days off. But yet you find time to give back. So just a big, big thank you from the entire Escoffier family, and from me.

Farmer Lee Jones: I’ve got to jump in there. I appreciate that. It’s so exciting to see the hope and the enthusiasm and the encouragement of the Escoffier students. It’s just as rewarding for me, hopefully, as it is for them to be able to talk to them, to be able to encourage them. It’s such an exciting time for them! To be involved in the Escoffier program and to be able to come out of this ready and be able to tackle the world and all of the culinary opportunities that exist right now. It’s very mutually beneficial. That’s what good relationships are built on.

The Importance of Locale

Kirk Bachmann: Beautifully said.

Because the story is so endearing and so beautiful, and I just love to listen: can you talk a little bit about your family? About the farm? How things got started? We’re past 30 years, right? Close to 40 years.

Farmer Lee Jones: You have to look first at where we’re at, the location. We all know the five Great Lakes, but Lake Erie is the shallowest of all the Great Lakes. We’re 2.9 miles inland from Lake Erie. It’s the shallowest, and consequently it’s the warmest. It’s what we hear of when people talk about a micro-climate and might not even understand. It’s something about the geography of the land that creates an environment that’s unique to that region. If you get five or six miles out from this area, the micro-climate does not effect it.

But it’s all old lake bottoms, some of the richest sandy loam in the world. At one point, there were 330 vegetable growing in this county. European settlers recognized this as an amazing growing area. This area was huge in grapes before Napa Valley was. It was steeped in tradition of growing vegetables.

A Brief History of Farming in the U.S.A.

We tend to be able to get on a freeway and go anywhere pretty quickly today. We take that for granted. But if you go back into the ‘20s, ‘30s, and ‘40s, roads and refrigeration had not developed to the point where there was a lot of outside competition. It’s ironic that today we’re working towards more of a regional distribution and regional and local food consumption, and consuming food that is more in our region. If you go back to the ‘30s, that’s what existed because the other options weren’t there. If you think about where we’re located: we’re an hour west of Cleveland, an hour east of Toledo. We’re right on Lake Erie, only two hours north is Canada. A couple hours north of Columbus. You had all these large metropolitan areas with big numbers of people and this amazing growing environment right in the middle. Those farmers did quite well.

My dad actually went to work for a very progressive grower. That progressive grower recognized the change that was coming, and that was that roads and refrigeration were improving and that larger farms could now become an impact on this region by doing it in mass production and cheaper. One by one, those 330 vegetable farms disappears, just like if the listeners can think about going back to their childhood and thinking about their hometown. Think about how many family-owned grocery stores were there when they were a kid that are no longer there because they’ve been replaced by a chain grocery store.

So my dad went to work for a very progressive grower that worked cooperatively with about 65 other growers and they were able to compete with those larger farms that were coming in and supplying product. My dad ended up buying that farm from [Mr. Nichols[00:09:26] and they had some very good years. We were farming about 1500 acres of fresh-market vegetables when I was 15 or 16 years old. My dad, interestingly, went to work for Mr. Nichols at 14 and then in his 60s bought that farm. Had some very successful years.

We were farming the way the universities were teaching. It was all about mass production. [Earl Butts,] maybe listeners have heard his name. He was a significant part of history, probably on the wrong side of it. I would say he was on the wrong side of it. His message was to get big or get out. Agriculture, at that time, was really the economic engine that drove growth in the United States. It was the one thing that we could compete on a world scale very, very efficiently with soybeans, wheat, and corn. We could ship them and compete anywhere in the world. We could produce very efficiently. It was all farming chemically, genetically modified crops.

Kirk Bachmann: And there was incentive to do that, right?

Farmer Lee Jones: Oh yeah, financial incentive. We were farming chemically. We were following the way the universities were teaching to farm at that time. Even though it kind of went against what my dad had learned from farmers in the past generation, he was going down that path.

Ultimately, we failed. Interest rates hit 22 percent and we had a very horrific hail storm that wiped the crops out. That was the straw that broke the camel’s back. When I was 19 years old, I stood and watched 25 years of my parents’ work auctioned off. All of our neighbors were there, all of our competitors. Everybody was there to celebrate our failure. I stood with my mom and dad, my brother and sister, and they auctioned everything right down to my mother’s car and our house. It was a horrific day. If I think about it for more than two minutes, I could be in tears.

Benefits of Being Old School

I think it also was a blessing in disguise. It was so severe that it made us make major changes. When we started rethinking what we were doing, it just didn’t make sense. We started looking back at agricultural books from 100 years ago. You can’t help but talk about nutritional levels. In 1930, the nutritional level in vegetables was 50 percent higher than it is today. We’re going the wrong direction with the chemical farming and genetic modification. As devastating as it was, it allowed us to reboot, if you will, and go back old school.

In a lot of ways, you’ll come to our farm and you’ll feel old school. You’ll see tractors that are 50 or 60 years old. Why? One, we know how to work on them. Two, they were smaller. They were lighter. You didn’t get the compaction on the soil. They just tend to make sense on small scale farming.

Kirk Bachmann: So your family had the wherewithal, despite the setback, to step back and do some additional research and figure out a different way. They didn’t give up, which is really, really a beautiful story.

Farmer Lee Jones: Some people said we were too stupid to quit! But it was in our DNA.

Kirk Bachmann: Passion.

Farmer Lee Jones: I’ve seen chefs in the same situation. They were on top of their game. They had three restaurants, or 30 restaurants and doing really well, and they lost everything. It’s in your DNA to start over. They can’t take your trade from you. They can take everything else, but they can’t take that, and they can’t take your passion.

We started over. But we did look back, and that certainly impacted greatly the direction we moved. We started back at farmers’ markets. We met a European influent [sic] chef. She was just on the farm last week. We had her come. I hadn’t seen her in 21 years. That day was the day that we opened the culinary vegetable institute and I only saw her for a few hours on that day. I hadn’t seen her then for 20 years earlier.

Kirk Bachmann: Is that where the name Chef’s Garden came from, through that process?

Farmer Lee Jones: Absolutely.

Kirk Bachmann: That’s just a beautiful story. Fast forward. How many years ago was that, when you restarted?

Farmer Lee Jones: 40 years ago.

Thoughts on Chefs who Elevate the Game

Kirk Bachmann: 40 years, okay. Fascinating.

Let’s talk a little bit about chefs. If you have that photo there, I want to go down that path. You can see Marco Pierre White over here. I have to tell you a quick story. My wife, Gretchen, and I were in Dublin years ago, and it was her birthday and mine. We’re walking down the street in downtown Dublin. I’m telling her about Marco Pierre White – his original restaurant, the book, who he was. And then I stop in my tracks. I look across the street, and I see Marco Pierre White Steakhouse. “What is happening here?!??” You can’t even be making this up! So we go over and make a reservation for the next night. This big photo here, when he was really young and in London, is the menu. He wasn’t there, but the food was exquisite. The service was over the top. He was one of the original bad boy chefs who knew what he wanted. You’ve met him, right? You’ve got the photo close by.

Farmer Lee Jones: We were actually at National American Culinary Federation convention, and [Jaime [00:15:25] and I got to speak.

Kirk Bachmann: There he is.

Farmer Lee Jones: We didn’t get to hear him speak. He was just being whisked out to his limo, and we happened to catch him for a quick photo. He reminds me a lot of Jean-Louis Palladin – who we met – from the Watergate Hotel, a highly talented chef. He was brought in from Europe to cook there. Marco Pierre White was certainly not bashful about saying what he thought, and neither was Jean Louis.

Kirk Bachmann: They made a big difference in the country. You’re really, really close with a lot of these chefs. Over on the other side of my office, I’ve got a framed menu. Another interesting story: years and years ago, I had my own restaurant. I started reading about this guy named Charlie Trotter and what he was doing in Chicago. This was before the day of Internet and all that. I picked up the phone. I guess my whole approach in my restaurant back then was I had menus from chefs from I admired adorning the walls. I was like, “You know, I’m going to get one of Charlie Trotter’s menus.” So I call the restaurant. A very lovely person answered the phone, took my message, and about a week or so later I got a little package. It had several menus. The one I framed is a vegetarian menu – way back then, 1994 –

Farmer Lee Jones: Way ahead of his time.

Kirk Bachmann: Charlie signed it at the top, “Keep on Cooking. Charlie Trotter.” One of my prize possessions. Talk a little bit about Charlie. You have a special relationship with Charlie over the years.

Farmer Lee Jones: We could talk for hours. Charlie Trotter did more for our family than we could ever repay. He was one of the first chefs in the country to have a pre-fixed vegetable menu. It was an offering. He was so far ahead of his time. He invited us on three different occasions to bring 20 people from the team here. We took Jose to J.C. Penney the day before and he bought his first suit. We rented a small bus. He invited us to come in for our team to experience the level of cuisine that they were doing.

It was so visionary when you think about it. When we got there, we were in training, and so was his staff. He had staff come out and talk about the dish they had prepared and why, and why it was important. He said, “Every one of you is going to ask two questions. We’re starting with you. Go.” We were there for nearly four hours.

When we got on the bus to go back, he was right there shaking everybody’s hand, thanking them for coming, handing them a gift bag with two books and a printed menu for the day. He gets back on the bus after everybody’s on, and he says, “I know Farmer Jones has told you that you all have to be on your best behavior, but after this bus starts moving, I want you to look under the backseat. There’s a case of champagne.” I don’t remember the kind that it was, but he said, “I expect it to be gone by the time the bus gets back home.” And the whole bus erupted in a cheer.

Kirk Bachmann: That’s something. That was Charlie. My executive chef here in Boulder, Bob [Schirner [00:18:46] and I both went to culinary school together. He went to Chicago and worked for Charlie for a couple of years. Boy, the stories! The stories are fascinating.

I remember one time I was there as a guest chef, but I was really honored just to hang at Charlie Trotter’s for a day. I got there early in the morning. They gave me my responsibilities, and then I cooked for my family who came in later that night. Long day. But the thing that really amazed me was the organization. Very little refrigeration. He was getting deliveries all day long.

What really fascinated me was the first service was at 5 and the second was at 7, something like that. Everything paused for a moment around 4 o’clock, and they completely cleaned the kitchen as if they were closing. And then they had family meal for all the staff. And it was important. It was really important. And then it started all up again. Way ahead of his time.

Talk a little bit about Curtis. Curtis Duffy, Michelin star restaurant tour, also very special to you. He has nothing but admiration for you, by the way.

Farmer Lee Jones: Great friend. I’ve known him since he was a line cook at Muirfield Village Golf Club down in Columbus, Ohio.

Kirk Bachmann: Wow! That takes us back!

Farmer Lee Jones: In the ‘8os. He worked under Chef John Sousa there at the Muirfield Golf Club. It’s just been fun to watch him rise to such a level of status, one of the greatest chefs in the country if not the world. He’s been to the farm and visited several times. I know that he came with the opening team of [Millennia [00:20:44] with [Grant Acketts [00:20:45] before they opened. He brought his opening team out and spent three or four days at the Culinary Vegetable Institute doing menu development and team building. Curtis was on that team.

Seven years later, Curtis brought his opening team. That’s really been the benefit of the Culinary Vegetable Institute is a place for chefs to come and do R&D and R&R. Jose Andreas brought 16 from his R&D team and they spent three days. They banged out an entire vegetable book in three days. They brought the journalist and the photographer, 16 R&D chefs and they developed recipes. He walked around in his bare feet and his pants rolled up.

Kirk Bachmann: At home.

Farmer Lee Jones: Curtis. I couldn’t say enough good about Curtis. he’s been a great friend. He’s a true professional, and it’s just an honor to know him and be a small part of what they’re doing. They’re doing some amazing things.

Kirk Bachmann: These relationships with great chefs who only want to serve the best products that they possibly can. Is it challenging at times? Are they demanding?

Farmer Lee Jones: Well, of course! Of course they are. They have to be. They’re under such an enormous amount of pressure, every single night. Charlie Trotter never served the same menu twice! I think Curtis operates under the same regime, just constantly upgrading. That expectation that it’s always got to get better. They’re pushing us, and that’s okay. We’re honored to be a part of their team. We know that if we don’t provide them with the products they need to be able to elevate themselves against the competition, what good are we? That’s important.

The Necessity of Tech

Kirk Bachmann: I want to segue and come back to the farm. Can you speak a little bit about technology? You spoke a lot about your roots and going back to what is right. How does technology and innovation play its part on the farm today?

Farmer Lee Jones: Some people say, when they come to the farm, that it’s like the Willy Wonka Chocolate Factory. You see a lot of widgets that we’ve built. Necessity is the mother of invention. A lot of the stuff that we’re trying to do, or trying to harvest, or trying to grow at a different stage or size than a traditional marketplace creates some necessity – to be able to produce mechanical equipment to be able to aid us.

Everything is ultimately harvested by hand. You’ll see old world, where we’re trying to get it as good as our grandparents were. But yet you’ll also see technology involved that our grandparents didn’t have available. It comes from scheduling planting product and trying to be able to track and have the right volumes of product at the right time and the right quality levels.

The technology to be able to expedite the product from – literally – the field. Imagine: this isn’t a giant Sysco warehouse. What they do is amazing, and nobody can do what they do. We’re kind of the opposite end of that. Our inventory, if you can visualize it, is all literally growing every single day. The inventory is in a field or in a greenhouse or in storage. We use the technology to be able to have that product available on a daily basis when the chef from Disney calls and says, “I want a petite Sylvetta aarugula.” And a petite is defining a particular size that we can go on any given day and be able to harvest the product at that size, and get it washed and cleaned and shipped and on their plate by the next day.

Technology really plays a huge part, and it’s evolving daily. It’s one of the most affordable thins in the world, this technology. It wasn’t so long ago, Chef, that we were using a Garmin. Who needs a Garmin today?

Kirk Bachmann: It’s on the phone.

Farmer Lee Jones: It’s all right there, in this little thing. It’s unbelievable. That technology is moving. As a small family farm, if we don’t embrace that technology, we’re behind. It’s an opportunity because it continues to be more and more affordable every day. We’ve looked and embraced the technology. it’s imperative for the survival and the regenerative nature of our farm to embrace the technology.

Nature’s Rhythm

Kirk Bachmann: You speak a lot of Mother Nature’s natural rhythm. Can you walk us down that?

Farmer Lee Jones: One of the most frequently asked questions is, “What’s your favorite vegetable?” My answer always is, “What season is it?” I think that even if we’re really in tune with our bodies – I don’t know if you’ve ever experienced this, but I know that I can attest to it – there are times when my body says, “You need Swiss chard. You need red beets. You need spinach.” Your body, if you’re really in tune with what you’re eating, it will tell you different minerals. I’ve read in a National Geographic where the women were actually eating soil because their bodies were craving a particular mineral. It was instinctive. Nobody would think, “Gee, I’m going to eat soil.”

There’s an intuitive nature about your body if you’re in tune with your body and listening. It will tell you what to eat. I guess the natural rhythm is that Mother Nature provides a beautiful menu for us. It’s not so much anymore, but early on, chefs would be frustrated with, “I’ve got to come up with a new menu. I don’t know what to put on the menu.” Look to Mother Nature and she’ll provide that for you.

Kirk Bachmann: She’ll tell you.

Farmer Lee Jones: What fish is in season? Is it poultry season? Is it pork season? Going into the vegetable, it’s such a beautiful rhythm. If you don’t have tomatoes on the menu now, don’t put them on at any other time, because they’re at their peak right now.

Kirk Bachmann: Let’s have asparagus in the spring rather than October.

Farmer Lee Jones: When asparagus is in season, we should eat it three times a day.

Kirk Bachmann: Yes we should!

Farmer Lee Jones: When it’s out of season, we should lust for it for ten more months!

Seeds of Hope

Kirk Bachmann: What about the current state of farmers in the United States? I don’t know if you feel comfortable talking about that. Are there challenges?

Farmer Lee Jones: Absolutely. I think there’s an argument to say that, without the capital to start, it’s very difficult. To start from ground zero and say that you’re going to farm. But it is possible. it’s one of those things that it takes very low dollars to be engaged and to be involved in agriculture. It’s one of those things. It’s probably more possible to get into agriculture than it would be to a restaurant.

I’m encouraged. There were more vegetables planted last year, more vegetable seeds purchased last year, more gardens planted last year than in the history of the United States. Even going back to the Victory Gardens after World War II. This pandemic has been devastating for all of us. We all have friends or family that we’ve lost, let alone the financial burdens of this and the pressure. I don’t think we’ll know fully how severe this thing was because the burdens it’s put on people and the stress levels it’s added, the anxiety levels. I think there’s a lot of negative that we can drum up around the ripple effect of this.

But I think we’ve got to look for those silver linings in any tragedy, and I’m hopeful. Kids emulate parents. You’re a family man, Chef, and I love to see your posts on Facebook with the kids at baseball. Kids emulate parents, and there were more parents planting gardens last year than in the history of the United States. Well, kids want to be out there helping in the garden. And if kids help plant a carrot, they’re a lot more excited about eating the carrot, pulling that carrot out and understanding where that carrot came from. Then cooking it and eating it. I’m encouraged. One of the little silver linings in this is that, just maybe, we’ve started a whole new generation of gardeners for the next 50 to 60 years. It’s a small thing. I’ll take it.

Kirk Bachmann: Beautifully said. I love that. Do you believe that the Chef’s Garden, so many years in the making, can serve as a model for others?

A Handful of Successes

Farmer Lee Jones: I’m always hesitant to say that. Maybe others might be able to say that better. We always say that we struggled to get our own house in order, much less to tell somebody else how to run their own household. Certainly people could benefit from all the mistakes we’ve made. My dad said we have to continue to make mistakes at a faster rate than the competition. He also said that we make mistakes well.

Kirk Bachmann: It’s how you learn.

Farmer Lee Jones: Even the book. People say, “how long did it take you to do the book?” Well, the short answer is two-and-a-half to three years. The long answer is 40 years. 40 years of trials, tribulations, mistakes, and hopefully a handful of successes.

Maybe there is. There were a lot of great growers way before us. I’d be hesitant to say, “Hey, look what we’re doing. Follow us. We know what we’re doing.” We make enough mistakes that I wouldn’t be too eager to say, “We’re the champions: follow what we’re doing.” I wouldn’t do that.

Kirk Bachmann: That’s the humble response that I knew I would get.

Farmer Lee Jones: The champion of mistakes. The champion of errors. The champion of failures. From that respect, we could tell you a lot of things not to do.

Product with Purpose

Kirk Bachmann: Michael Jordan missed more shots than he made.

Every few weeks you take the time to speak with me and a new group of Escoffier students that are just about to go out onto their externships. Right now we do that on Zoom together. It’s really a nice time. It’s a time that I always look forward to. The students typically receive a little package of vegetables from the farm right before we get on the call. You talk about farm to table, you talk about the programs, and you talk about the importance of exposure to everything we’re talking about here today.

Farmer, how important is it in your mind for young culinarians to fully understand where their food comes from? Not only where, but how that food is produced the right way? Some many people don’t have exposure to understanding that.

Farmer Lee Jones: I can tell you there’s a lot of food that’s produced in America where the people don’t have any idea where it’s coming from. They are able to produce literally millions and millions of plates of food without that knowledge. That being said, is it a push through or a pull through? I think that the consumer is more savvy, more attuned, more interested, more knowledgeable about where food is coming from than ever before in the history of the United States.

We’d let that slip away from us. It existed in America. We knew where the chicken was coming from. We knew where the vegetables were coming from. Was it our fault? Can we blame somebody for why we let that slip away? The frozen TV dinners. You remember those as a kid just like I do. My mother thought it was the greatest thing since sliced bread because it was two people in the family working outside of the home. Where my grandmother’s generation stayed home. It was gender specific at that time. Grandma stayed home, and Grandpa worked outside at another occupation and she took care of the family and cooked, and in many cases, took care of the garden. We let that slip away.

But I think that the consumer today, the next generation – I don’t know, is that the X generation, or Y?

Kirk Bachmann: Or are we to Z, or starting back over at A?

Farmer Lee Jones: People want to know where their food’s coming from. They are interested in how the environment is taken care of, how the people on those farms are being taken care of. Are they being paid a fair wage? Is the food being grown the right way? It’s product with purpose. That goes so much more than the depth of the food.

I think there’s a tremendous opportunity for the culinary students coming out of Escoffier and any of the culinary schools to really make a connection for themselves personally to know where the food’s coming from, but also to communicate that out. Because the consumer is interested in that, and they want to know all of those things. It can add so much value to the experience for the end consumer to be able to know. We can add value to that experience. If we were just satiating our bellies, we would go to the grocery store, we’d go home, and we’d cook. If you’re going out, you’re going out for the experience of that. You’re satiating the belly, of course, but the psyche, the mind. You want to support something that supports the beliefs that are important to you. It’s product with purpose, and it’s never been more important than it is today.

Kirk Bachmann: I love that. Product with purpose. I wrote that down. That’s beautiful.

The Instagram handle: shameless plug.

Farmer Lee Jones: @farmerleejones We would love for you folks that are listening to keep us posted. Tell us what you’re doing and where you’re at. The future for the culinarians in the world and in the United States right now has never been more opportunistic. The pandemic, again, I’ll go back to it. Horrific! But the creativity in the culinary world just blows my mind. Think of the ways that we found to be able to get food, to create an experience for people that were kind of on lockdown. Restaurants found a way to be able to produce food. A lot of those aren’t going to go away. The restaurants are returning, but all those other tentacles that we figured out – we’ve multiplied the job opportunities through the pandemic to 2021 by ten-fold. There’s never been a more exciting time to be an Escoffier graduate than right now!

Farmer Lee’s Ultimate Dish

Kirk Bachmann: I love it. There is no greater passion than Farmer Lee.

Farmer, the name of the podcast is The Ultimate Dish. We’ve come to that point in the show to ask you: what is the ultimate dish?

Farmer Lee Jones: I would ask you what season we were in.

Kirk Bachmann: I knew it! I love it!

Farmer Lee Jones: Since I know that it is peak August, we’ve had 90 degrees day after day. You go out into the field and the tomatoes are ripened from the summer sun! And you have to have a hanky in one hand and a tomato in the other, because the juice is just dripping down your chin! It’s got to be a BLT! That’s the only way to go.

Kirk Bachmann: I love that! A BLT, that is perfect! Absolutely perfect. I wasn’t expecting that. That is awesome. I thought you were going to just stay with the tomato.

Farmer Lee Jones: No, it’s a BLT.

Kirk Bachmann: I love it. Farmer, thank you so much for being with us today. I look forward to our next chat. We love you. I love you. Be safe. Be healthy. Thanks again.

Farmer Lee Jones: I gotcha. Thanks for having me on. Have a great day.

And thank you for listening to The Ultimate Dish podcast, brought to you by Auguste Escoffier School of Culinary Arts. Visit Escoffier.edu/podcast where you’ll find any materials mentioned during the podcast, including notes, links, and other resources. You can also browse other episodes and subscribe.